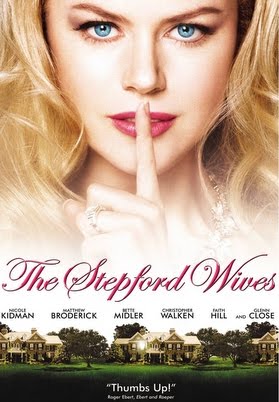

Paramount Picture’s The Stepford Wives revolves around Joanna, a Manhattan career woman who, after being fired from her job, moves her family to the chic Connecticut town of Stepford. All of the women of Stepford are robotically blissful, tirelessly subservient, and impossibly flawless. Quite the opposite of Joanna’s independent, assertive nature and somewhat masculine appearance which goes against this dominant ideal. (Sellnow, 93) Neither the men nor the women work and the men’s expectations of their wives assume that they spend the day at home cooking, cleaning and awaiting their husbands’ return to feed and seduce them on demand. This suggests that being a ‘Stepford Wife’ is the normal, appropriate and desirable way for a woman to behave in society. Targeted towards a young female audience, this film depicts a subverted oppositional reading in it’s use of exaggerated forms of perceived female normalcy which outrightly mock and reject patriarchal hegemony. With a touch of horror, the female audience is forced to question whether these taken-for-granted beliefs are truly the perfect way things ought to be, or, if society is just adhering to frightening ideologies created by a patriarchal hegemonic system.

The clip begins with Joanna being driven through the perfectly groomed streets of Stepford by a well-known resident; Claire. Upon passing a secluded, sturdy, dark stone building up on a hill, Joanna soon finds out that this is the Stepford Men’s Association. As the women arrive at the Simply Stepford Day Spa for women (a street-level, white structure surrounded by an angel fountain and pink flowers) viewers are immediately reminded of the ideological belief that even the separate associations to which men belong are strong, powerful, and above the ‘pretty’, trivialized organizations of women. Subjects versus Objects.

As Joanna enters the spa to ‘work out’ in sweat clothes she is greeted, in perfect unison, by the ‘Stepford Wives’ ready to begin their aerobics class in dresses and stilettos with flawlessly coifed hair and impeccable make-up; seemingly appropriate exercise attire for women. Bewildered, Joanna questions Claire and is met with a response of equal surprise in reference to her: “…why imagine, if our husbands saw us in worn, dark, urban sweat clothes, with stringy hair and almost no make-up!” (The Stepford Wives, 2004) This reinforces the audience’s initial view of dowdy, outspoken Joanna as the undesirable anti-model compared to the desirable model(s) who follow the rule that women “are supposed to be objects who should look pretty and act only as supporters of male agents and male agendas”. (Sellnow, 94)

The ladies then engage in a series of exercises based on household tasks and appliances suggesting that this is the appropriate ladylike form of exercise and consistent with the created dominant ideology of a female’s single value; a homemaker. As the scene continues, viewers start to identify with Joanna as their views of the model and anti-model begin to reverse. They realize that something is not right about the behaviours of these women and see Joanna as a woman with a brain and a spine; the true model they want to be like.

At first glance, this film appears to portray the message that being a ‘Stepford Wife’ is the normal, appropriate and desirable way for a woman to behave in society. However, a deeper analysis uncovers the true message hidden in the subtext: the taken-for-granted beliefs of how a perfect woman should behave in society are, in reality, only ideologies created by a patriarchal hegemonic system by which we allow ourselves to comply.

Works Cited:

Sellnow, Deanna D. The Rhetorical Power of Popular Culture. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications, Inc., 2010. Print.

“The Stepford Wives (2004)”. IMDb, n.d. Web. 24 Feb. 2013

“The Stepford Wives (2004)”. YouTube, n.d. Web. 24 Feb. 2013

“The Stepford Wives (2/8) Movie CLIP – Clairobics (2004)”. YouTube MovieClips, 8 Feb. 2012. Web. 24 Feb. 2013.